Carved for Sound: How the Acoustic Archtop Guitar Keeps Swinging

In this feature, we’ll trace the history of the acoustic archtop guitar—from its 19th-century origins and golden-era prominence to its postwar decline and modern-day revival.

Although often dubbed a “jazz box,” the acoustic archtop guitar is far more versatile than the nickname suggests. From blues to country to early rock ’n’ roll, it has found a place in nearly every genre. Sam Chatmon, who recorded with the Mississippi Sheiks in the 1930s and was later rediscovered during the folk revival, played expressive Delta blues on his early-1930s Gibson L-4. Maybelle Carter helped define the sound of country music with her trademark Carter scratch, played on a 1930 Gibson L-5.

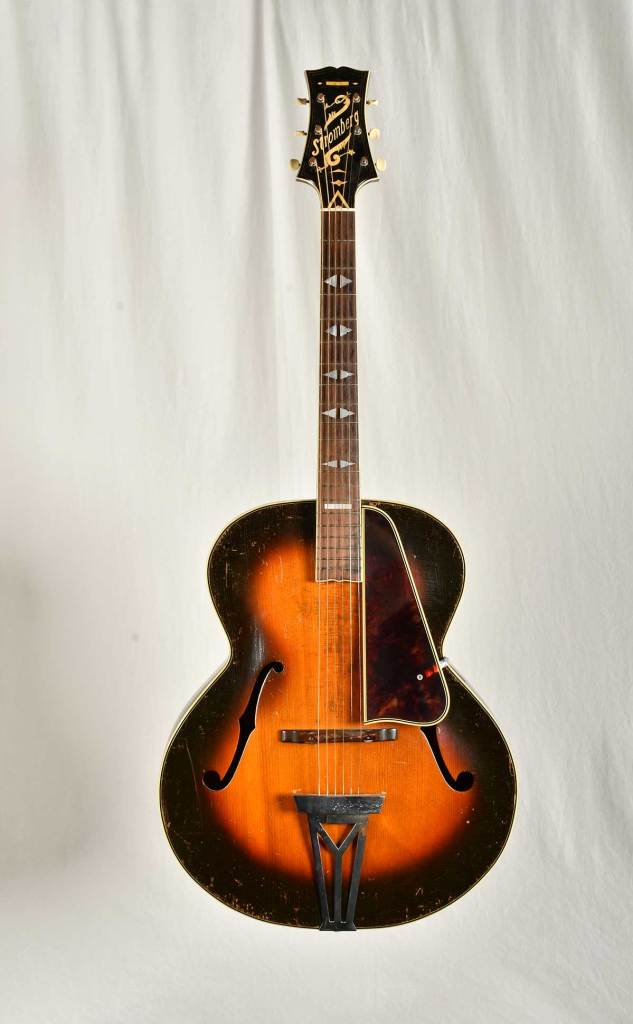

Western swing legend Ranger Doug Green has long favored Gibson and Stromberg archtops for his work with Riders in the Sky and the Time Jumpers. Bill Haley rocked around the clock on a series of Gibson L-5s throughout his career. And of course, countless guitarists have explored the instrument’s full harmonic range in jazz settings—from Eddie Lang to more recent acoustic stylists.

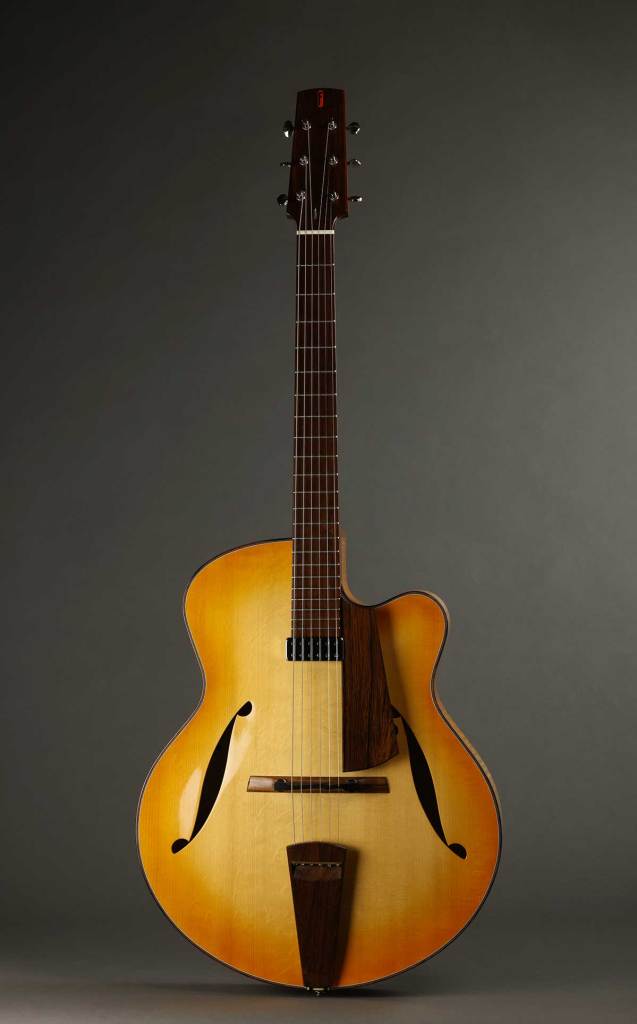

With its carved spruce top, maple back, floating bridge, and f-holes, the archtop was built for power and projection. Its voice is bold and percussive, with strong attack and limited sustain—perfect for driving rhythm, but equally suited to melodic lead lines and lush chord voicings. It’s a different beast than the flattop, and that difference has made it indispensable in certain musical settings.

In this feature, we’ll trace the history of the acoustic archtop guitar—from its 19th-century origins and golden-era prominence to its postwar decline and modern-day revival—highlighting the builders, players, and innovations that shaped this distinctive instrument.

Gibson’s Breakthrough

The archtop first became widely popular with guitarists in the late 1920s, but its story stretches back a full century earlier. The first hundred years of its development are a chronicle of skilled luthiers almost—but not quite—arriving at a workable design. Builders and players alike longed for an instrument that combined the guitar’s sweet, harmonically rich tone with the power, clarity, and projection of a violin or other bowed instrument. But no one quite landed on the solution.

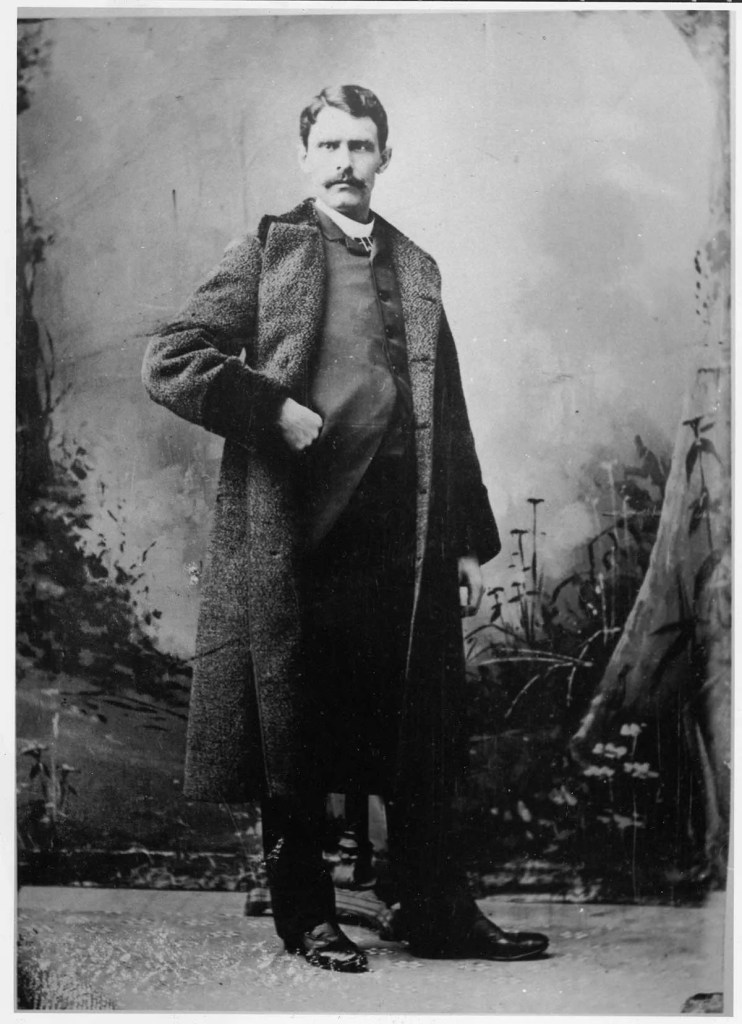

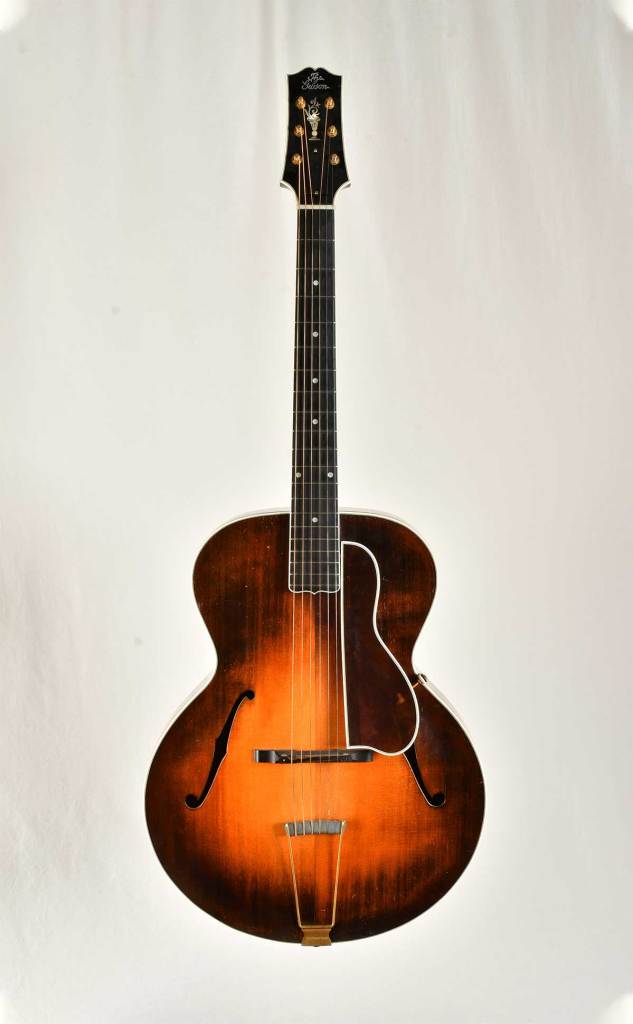

That began to change in 1898, when a luthier in Kalamazoo, Michigan, named Orville Gibson received a patent for a mandolin with an unusual construction style. His approach set in motion a series of developments that would eventually lead to the modern archtop guitar. As early as the 1890s, Gibson was carving the tops and backs of his instruments, rather than bending or bracing them. His mandolins featured a floating bridge and tailpiece—standard fare for the time—but his guitars were fitted with fixed bridges and bridge pins, blending carved-top construction with the setup of a typical flattop.

Gibson’s designs also included one highly unconventional element: the neck, sides, and back were carved from a single piece of wood. He believed that joints, kerfing, and braces dampened an instrument’s resonance. His mandolin necks were even hollow, which he claimed further enhanced vibration.

In 1902, five Kalamazoo businessmen purchased Gibson’s patent and founded the Gibson Mandolin-Guitar Manufacturing Company. They thought his radical mandolin design would appeal to players in mandolin orchestras—then popular across the country—who were tired of cumbersome bowl-back instruments. At first, the company built instruments to Gibson’s specifications, but it soon became clear that carving necks, backs, and sides from a single block of wood was wasteful and expensive. Over the next few years, they began to refine and simplify the construction process.

Gibson, unhappy with the direction the company was taking and uncomfortable in a factory environment, left by the end of 1903. Sadly, his health declined over the next several years, and he died in 1918 after a long illness.

By 1908, George D. Laurian, the company’s general superintendent, had completed a major refinement of Gibson’s designs. He abandoned the one-piece construction approach in favor of more traditional methods using separate components. He also altered the neck angle on all models, tilting it back to raise the bridge height and increase downward pressure on the top—improving both tone and volume.

Refining the Design

In its first catalog from 1903, Gibson listed 21 different models of six-string guitar—though it’s uncertain whether every variation actually made it into production. All featured fixed bridges with bridge pins, much like a flattop.

By 1908, it became clear that the company had been overly optimistic about guitar sales, and Gibson pared its offerings to five models: the L-1, L-2, L-3, L-4, and the Style O Artist. The Style O stood out with a dramatic scroll carved into the upper bout—a nod to the company’s F-style mandolins—and included a cutaway for easier access to the upper frets.

ADVERTISEMENT

Around the same time, Laurian replaced the fixed bridge design with a floating bridge and tailpiece. Though the bridge was not yet height adjustable, it was compensated for better intonation and introduced a new two-footed design that would become the industry standard for archtop guitars. These innovations didn’t lead to a spike in guitar sales, but the key elements of the modern archtop were now in place—waiting for the next wave of refinement.

Mandolins, meanwhile, were selling briskly through the 1910s. But following World War I, that began to change. Mandolin ensembles were increasingly seen as old-fashioned, and with the spread of radios and phonographs, more people could listen to music at home without needing to play an instrument themselves.

Sensing the shift, Gibson set out to revitalize its mandolin business. Around 1919, general manager and co-founder Lewis Williams hired Lloyd Loar as a design consultant. An accomplished musician and acoustic engineer, Loar had been writing music for Gibson since 1911 and was now tasked with developing a new line of mandolin-family instruments.

Loar’s exact role in shaping the Master Model instruments is still a matter of debate. He signed and dated labels inside each instrument stating that the “top, back, tone-bars and air-chamber of this instrument were tested, tuned and the assembled instrument tried and approved.” How literally to take that claim is unclear.

It’s also unknown whether he personally introduced now-standard features like f-holes and cantilevered fretboards. What is clear, though, is that both Loar and the company gave relatively little attention to the guitar version of the Master Models—at least at first.

Overlooked and Undersold

Thaddeus McHugh, who became Gibson’s general superintendent after Laurian’s departure in 1915, typed detailed specifications for every model in 1919. When he updated those notes in 1922 to include specs for the new F-5 mandolin, H-5 mandola, and K-5 mandocello, there was no mention of the L-5 guitar. And when Gibson released its brochure announcing the Master Model line, the guitar didn’t appear there either. The focus was entirely on mandolins.

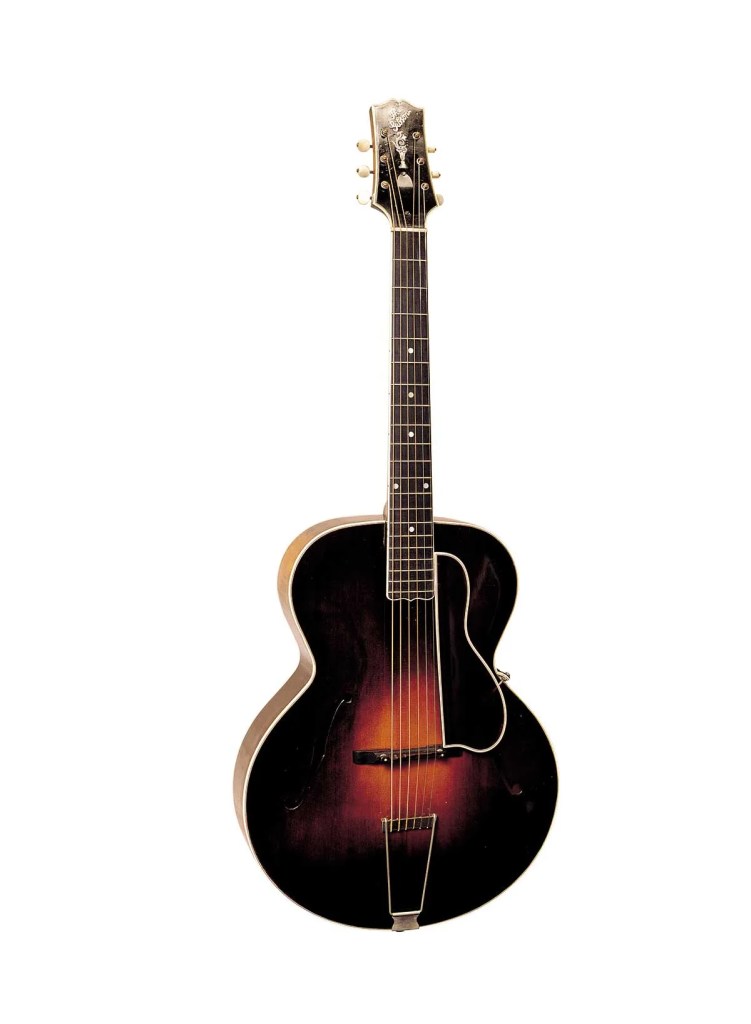

The F-5 was the first of the Master Models to launch, debuting in 1922. The H-5, K-5, and L-5 followed in 1923. The L-5—or, in full, the Gibson Master Guitar Style L-5 Professional Model—was a striking instrument. Measuring 16 inches across the lower bout, early versions featured carved birch backs (later switched to maple), a carved spruce top with two small unbound f-holes, and a Cremona Brown sunburst finish, named in honor of the Italian city where Stradivari and other legendary luthiers once worked. It also included two recent McHugh inventions: an adjustable-height bridge and an adjustable truss rod. The neck was adorned with simple pearl dot inlays and fitted with tuners featuring pearl buttons.

As fine as these Master Models were—and they’re now considered among the best instruments Gibson ever made—they didn’t achieve their intended goal. The effort to revive the mandolin market fell flat. Sales were dismal. Estimates suggest that during the line’s two-year run, Gibson sold around 275 F-5 mandolins, 17 H-5 mandolas, 9 K-5 mandocellos, and just 35 L-5 guitars.

On October 3, 1923, Lewis Williams resigned from the company he had co-founded. A few months later, Lloyd Loar also left. Meanwhile, Gibson’s banjos were quietly gaining momentum. By 1925, under new general manager Guy Hart, Gibson had pivoted decisively toward the banjo market. The company overhauled its line and, by 1927, was producing some of the finest banjos of the era. For the rest of the decade, most of Gibson’s ads in fretted instrument magazines like The Cadenza and The Crescendo were devoted to banjos, while guitars and mandolins faded into the background. The F-5 didn’t appear in a single ad for the remainder of the 1920s.

The L-5 Catches On

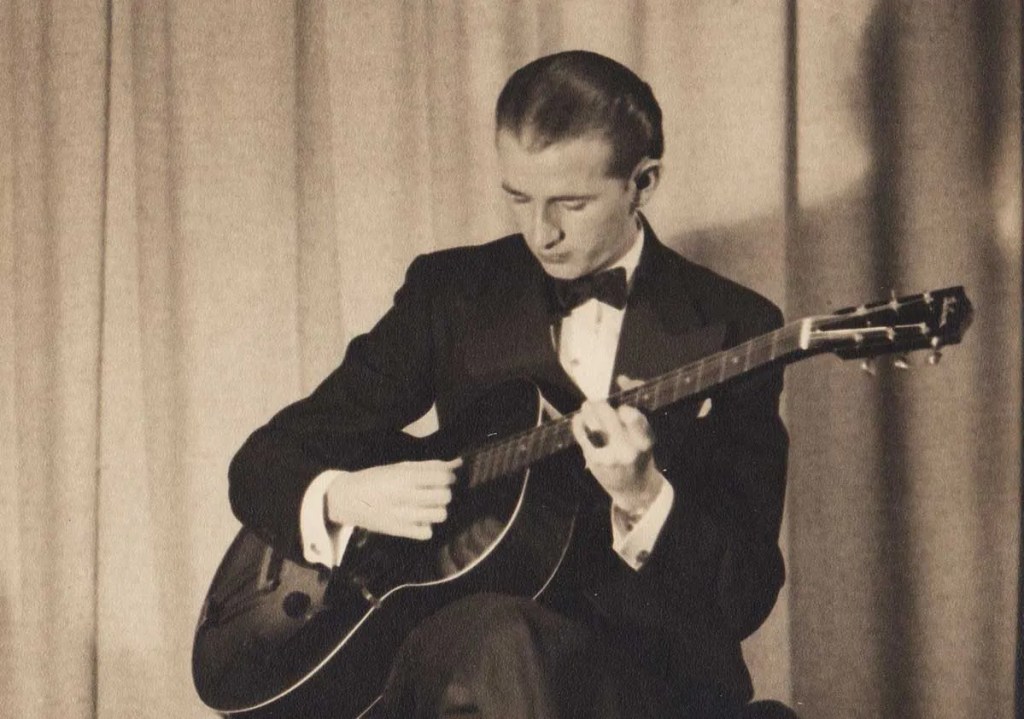

While Gibson was pouring its energy into banjos, guitarists quietly began to embrace the L-5—a commercial flop at launch—as the ideal instrument for backing singers and holding down rhythm in larger ensembles. One of the first to see its potential was Nick Lucas, a popular vaudeville performer who accompanied himself on guitar. Lucas was pictured with an L-5 in Gibson’s 1926 catalog, suggesting he’d picked one up by then.

Another early adopter was Eddie Lang, often hailed as the father of jazz guitar. Lang was among the first players to record single-string jazz solos, but he was equally admired for his inventive rhythm playing and nuanced accompaniment. He began his recording career on a Gibson L-4, eventually switching to the L-5 around 1928.

Lang became one of the most in-demand studio guitarists of the 1920s. His recordings span genres and artists: pop singers like Bing Crosby, Annette Hanshaw, and Cliff Edwards; blues icons like Bessie Smith and Lonnie Johnson; and virtually every major jazz player of the era, including Bix Beiderbecke and Joe Venuti. Tragically, Lang died in 1933 at just 30 years old, following complications from a tonsillectomy.

For Gibson, there could have been no better ambassador. Lang showcased the L-5’s versatility—as a solo instrument, a rhythm machine, and a musical chameleon that fit into any setting. And as the 1920s drew to a close, Gibson would soon need that kind of validation more than ever.

A New Rhythm King

By the mid-1920s, at the height of the Jazz Age, the banjo was a staple in nearly every band. Its bright, brash tone cut through the mix and translated well with the rudimentary recording technology of the era. But as that technology improved, less strident instruments became easier to capture, and public taste began shifting toward smoother, more refined sounds.

The writing was on the wall: the banjo’s days as a rhythm king were numbered. The guitar was poised to take its place, just as the banjo had once edged out the mandolin. But in the late 1920s, neither musicians nor builders had settled on the right kind of guitar for the job. Tenor guitars had a brief moment—essentially banjo necks on guitar bodies—but lacked volume and punch. National’s metal-bodied Tricone offered volume in spades, but found favor mostly among Hawaiian steel players. Epiphone’s asymmetrical Recording series looked bold but didn’t catch on. Martin introduced its 14-fret Orchestra Model, but it, too, failed to find traction in jazz and dance bands.

That left the L-5, which turned out to be the perfect rhythm guitar for the big band era—powerful and cutting, but without the banjo’s clatter. One way to trace its rise is through Gibson’s own catalogs. In the 1930–31 edition, the bold proclamation “America Hails the Banjo” appeared on one of the first pages, followed by 18 pages of banjo models before guitars even showed up. But in the 1932 catalog, the L-5 took pride of place as the lead instrument.

ADVERTISEMENT

Gibson had the archtop field to itself—but only briefly. In 1931, Epiphone launched nine archtop models across various price points, including the Deluxe, a direct competitor to the L-5. That same year, Elmer Stromberg began crafting archtops in Boston. And in 1932, John D’Angelico opened his shop in New York, hand-building his own interpretation of the L-5. Even Martin entered the fray with a line of arched-top, flat-back guitars, but they lacked the volume and projection of carved instruments and never caught on.

Also in 1932, Harmony introduced the Cremona, an inexpensive archtop that marked a turning point. Harmony specialized in budget instruments—but built more of them than anyone. In the 1920s, the company claimed to have produced half of the guitars and ukuleles sold in the United States. If Harmony was making archtops, there was no doubt: the instrument had officially arrived.

Bigger and Bolder

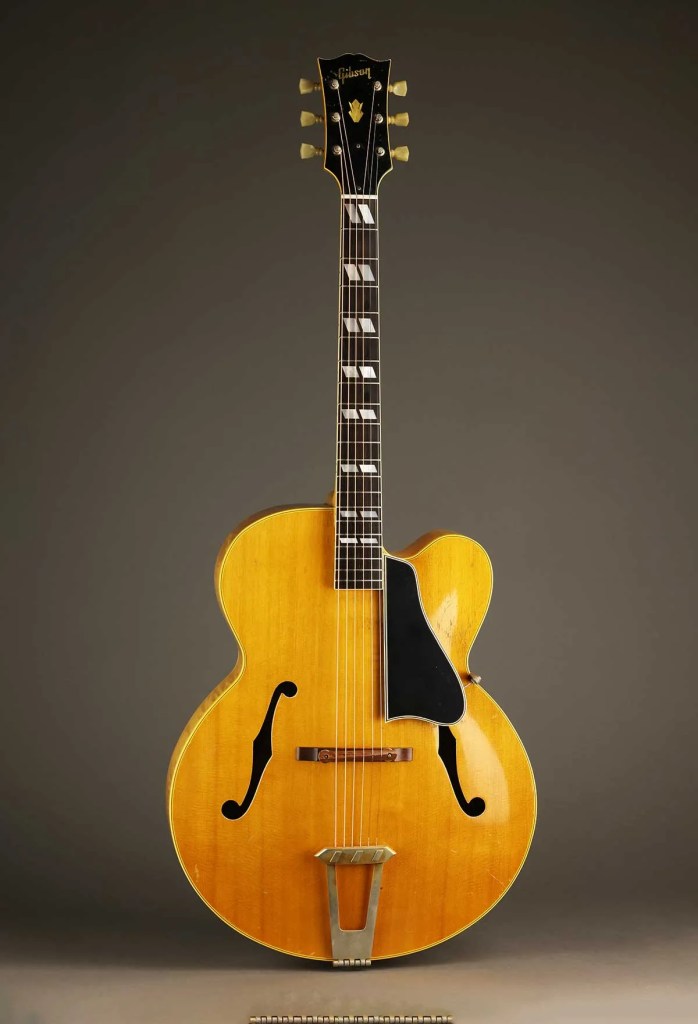

As the archtop guitar gained traction, musicians began asking for louder instruments with more projection—something that could hold its own against horns and saxophones in big band settings. In 1935, Gibson answered with the Advanced L-5, featuring a 17-inch lower bout. That launch set off what became an archtop arms race.

Epiphone responded by redesigning the Deluxe with a 17-3/8-inch lower bout. When Gibson unveiled the 18-inch Super 400 in 1934, Epiphone countered in 1935 with the Emperor, measuring 18-1/2 inches. D’Angelico joined the fray with the 17-inch Excel, later followed by the 18-inch New Yorker. And in the late 1930s, Elmer Stromberg went even further, introducing the Master 300 and Master 400—both boasting an imposing 19-inch lower bout. Other builders seemed content to let Stromberg have the last word in the size department.

At the same time, Gibson expanded its archtop lineup. In the early 1930s, it introduced the L-7, L-10, and L-12—simpler, more affordable versions of the L-5. These models began with 16-inch bodies, which were enlarged to 17 inches in 1935. That same year, Gibson updated the L-4 to include f-holes, though it kept its 16-inch body. Also added to the catalog were the L-30 and L-37, compact 14-3/4-inch guitars priced at $30 and $37 respectively, and the L-50, a 16-inch model that sold for $50. In contrast, the L-5 came in at $275, and the Super 400 topped the line at $400.

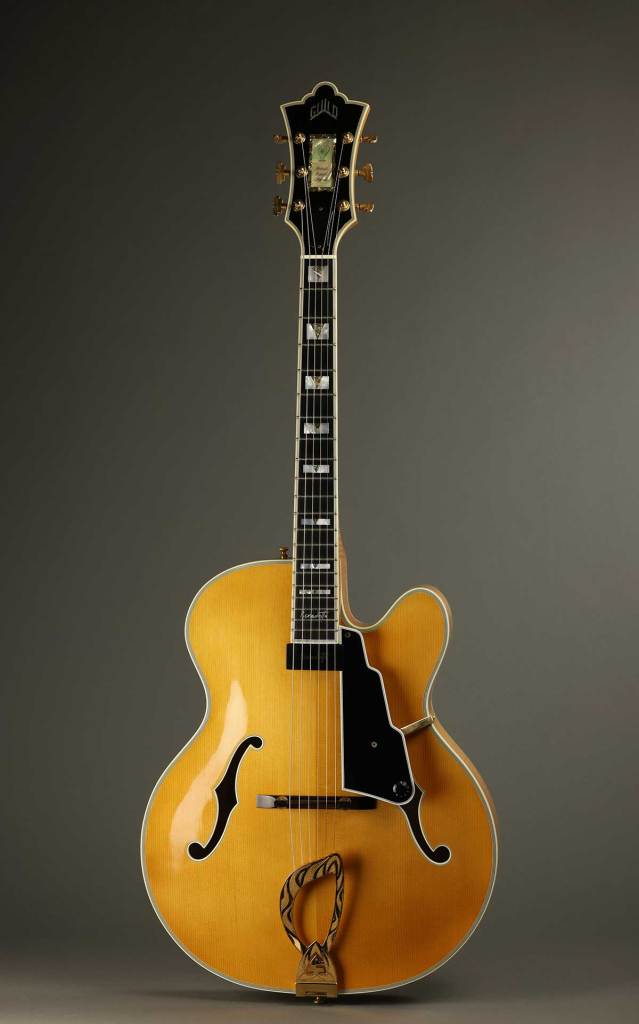

By the mid-1930s, archtops were available in a wide range of sizes and price points from Gibson and a growing roster of builders. Gretsch entered the scene in the late 1930s, and in the early ’40s launched the Synchromatic line, known for its dramatic cat’s-eye soundholes.

Budget makers like Kay and Regal followed suit, producing numerous models—often rebranded for mail-order catalogs, department stores, and music shops. Even Gibson joined the badge-engineering trend, building guitars under names like Kalamazoo, Recording King, Cromwell, and others.

Swing and Shift

Players embraced the new generation of archtops by turning rhythm guitar into a true art form. It’s no exaggeration to say that guitarists put the swing in swing music. Musicians like Allan Reuss (Benny Goodman), Fred Guy (Duke Ellington), and Freddie Green (Count Basie) laid down a steady four-to-the-bar pulse that kept the band moving while providing a rich harmonic bed for soloists. This kind of playing demanded stamina, precision, and a deep command of harmony.

Others, like Carl Kress, Dick McDonough, and Fred Van Eps, carried forward the solo and duet traditions pioneered by Eddie Lang in the late 1920s—expanding the archtop’s possibilities beyond the rhythm chair.

By 1936, even in the depths of the Great Depression, business was good for most guitar makers. Archtops were available at every price point and had become central to the most popular music of the era. But change was on the horizon. In December of that year, Gibson introduced the ES-150—its first electric Spanish-style guitar—and with it, a signal that the era of the purely acoustic archtop was beginning to wane.

Magnetic pickups weren’t new; Rickenbacker had released its aluminum A-22 “Frying Pan” lap steel in 1932, and other companies, including Gibson, had followed with electric Hawaiian models. A few builders had even dabbled in electrifying guitars with regular necks, but none had made a lasting impact—until the ES-150.

The guitar world responded cautiously at first. But in 1939, Charlie Christian arrived. His blazing single-note lines showcased exactly what the electric guitar could do. It’s hard to overstate his impact: before Christian, the most forward-thinking players used acoustic guitars. After him, they plugged in.

The ES-150 and Christian’s groundbreaking playing didn’t kill off the acoustic archtop, but they made the future clear. World War II further slowed guitar production as materials were rationed and factories shifted to wartime manufacturing. When the war ended, the music scene had changed. Big band swing was fading fast, and the new sounds on the horizon—bop jazz, rock ’n’ roll, and polished pop—had little room for acoustic rhythm guitars.

ADVERTISEMENT

As demand declined, manufacturers adjusted course. Gibson began producing more electric archtops, and in 1952 introduced the solid-body Les Paul. Fittingly, Les Paul himself had come up playing a 16-inch dot-neck L-5 in his early days as a country performer under the name Rhubarb Red.

Gretsch also moved into electrics, as did Epiphone. There were still musicians playing acoustic archtops, but more and more were fitting them with floating, removable pickups like the DeArmond Rhythm Chief. The days of the purely acoustic archtop guitarist seemed numbered.

Happily, John D’Angelico continued building fine archtops in his small New York shop. In 1952, Jimmy D’Aquisto began working with D’Angelico and stayed on until the master’s death in 1964. D’Aquisto completed the final ten instruments D’Angelico had in progress, then launched his own line—ushering the archtop into new aesthetic and sonic territory.

As mentioned earlier, you can trace an instrument’s popularity through its position in Gibson catalogs. In 1942, the L-5 and Super 400 still appeared at the front. But over the decades, they drifted further and further back, and by 1967, the acoustic archtops shared the final pages—behind tenor guitars, classical guitars, and even banjos, which were enjoying a folk revival bump. A bittersweet placement, considering these were the very instruments that had led Gibson’s first catalog in 1902.

Luthiers Advance

Even as major manufacturers pulled back from acoustic archtop production, a dedicated group of individual luthiers carried the tradition forward. Robert Benedetto built his first archtop in 1968 and quickly gained a reputation for excellence, crafting guitars for players like Bucky Pizzarelli, Chuck Wayne, and Joe Diorio. He began building at a time when the art of the acoustic archtop was in serious decline. In 1992, he launched a seminar to teach the craft to a new generation of builders, and in 1994 published Making an Archtop Guitar, a detailed guide that became essential reading for both aspiring and seasoned luthiers.

Meanwhile, a different thread of revival emerged from the bluegrass world. In the 1970s, as the genre surged in popularity, demand grew for high-quality mandolins—especially the prized Lloyd Loar–era Gibson F-5s favored by Bill Monroe. Original examples were scarce and later Gibsons had slipped in quality, prompting a new wave of builders to fill the void.

Luthiers like John Monteleone, Steve Grimes, and Stephen Gilchrist (who began building in the early 1980s) stepped in—not just with mandolins, but guitars as well. Like Orville Gibson decades before, these craftsmen felt compelled to make both. Their exceptional workmanship, along with a grow-ing appreciation for vintage archtops, helped reignite interest in the form. By the mid-1980s, building a great archtop had become a badge of honor—a pinnacle achievement for serious luthiers.

Some, like Richard Hoover at Santa Cruz Guitar Company, dabbled in archtops before returning focus to flattops. Bill Collings earned a quiet but loyal following for his archtops, producing just one or two a year until his death in 2017. Steve Andersen began with flattops and mandolins, but after his first archtop was met with acclaim, he shifted almost entirely to that style by 1990.

ADVERTISEMENT

In 1995, the archtop world lost one of its giants when Jimmy D’Aquisto passed away. Having apprenticed with John D’Angelico, D’Aquisto expanded on his mentor’s work. His early guitars echoed D’Angelico’s art deco aesthetic, but over time he developed a sleeker, more contemporary look. With fewer players demanding the brute volume once needed to power swing bands, D’Aquisto was free to focus on balance, subtlety, and sonic nuance.

His influence ran so deep that guitar collector Scott Chinery commissioned a tribute. In 1994, Chinery had ordered a Centura Deluxe from D’Aquisto, a bold 18-inch archtop with a striking blue sunburst finish. After D’Aquisto’s death, Chinery invited 19 contemporary builders to each craft a tribute guitar with two requirements: the instrument had to measure 18 inches across the lower bout, and it had to feature the same blue finish. Beyond that, creativity was encouraged—and the luthiers delivered. The Blue Guitar Collection was completed in early 1997 and first exhibited at the Smithsonian.

The Blue Guitar project became a turning point, simultaneously honoring the golden age of the archtop and pointing to its future. In the years since, interest in archtops has continued to grow. For a time, scarcity and high prices limited access—solo builders could only make a handful per year, and top-shelf vintage models routinely reached five figures. But eventually, high-quality, lower-cost options began to appear. Companies like Epiphone, Godin, the Loar, and Eastman stepped in with accessible models that opened the door to a wider range of players.

Still Swinging

More and more players have embraced the acoustic archtop in recent years. Musicians like Matt Munisteri, Nick Rossi, and Jonathan Stout have delved deep into the early jazz and swing styles first defined on these instruments. While most modern jazz guitarists have stuck with electrics since the Charlie Christian era, Julian Lage has occasionally brought out a 16-inch L-5 for his acoustic explorations.

On the country and Americana side, artists like David Rawlings, Logan Ledger, and Pokey LaFarge have all tapped into the archtop’s vintage voice. Rawlings, in particular, is known for playing an early 1930s Epiphone Olympic—a small-bodied model that was the most affordable in Epiphone’s lineup at the time. His choice underscores a simple truth: you don’t need a high-end archtop to make great music. Perhaps ironically—or at least fittingly, given his visibility—original Olympics have skyrocketed in value; a clean example can now fetch as much as a Gibson L-5 or Epiphone Deluxe from the same era.

Today, more builders are crafting acoustic archtops than ever before. While the instrument may not enjoy the ubiquity it had in the 1930s, it continues to appear in the hands of players across styles and generations. With so much renewed interest and creative energy around it, one thing is clear: the acoustic archtop is here to stay.

This article originally appeared in the September/October 2025 issue of Acoustic Guitar magazine.

Great article! I love archtops.

My first was an Epiphone Olympic that had been around the block many times, with severely divoted frets. I refretted it myself with great result but sold it later to pursue a flattop I wanted at the time. No problem with the refretting but I realized I had too many other interests to get into repair or building.

I later bought a used Steve Andersen Vanguard that was apparently modified for hard rock playing: a hot Stuart Duncan humbucker and stuffed with acoustic foam, apparently to reduce feedback. It sounds great with a PAF Humbucker an I still have it.

In 2017 Andersen built me a custom Model 16 that is fantastic. I love playing it and it’s a work of art as well.

I do love archtops!

D’Angelico archtops were always a dream guitar growing up. Pictured on the Mel Bay Chord System for Rhythm and Orchestral Guitar book I studied from, I’d see one everyday when practicing. At some point in my teens I traded for a ‘61 Gretsch Country Club but it wasn’t the dream guitar and eventually I sold it. In the 90’s a Japanese company called Vestax produced some fine D’Angelico replicas. I purchased an NYL-4, the 18” New Yorker. It’s a fine instrument. But what turned out to be my main gigging instrument is a Hofner Jazzica (also from the 90’s). This article did not mention any of the European archtop builders, of which there were and are many.

As a collector of European archtops I can recommend the recently published ‘German Jazz Guitars: The Archtop Guitar in Post-War Central Europe’. Written by Cameron Brown and Stefan Lob and published by Unicorn, UK. It is beautifully illustrated.

All very well to say Gibson did it first, but I’m restoring an arch top guitar from 1853. Built in London buy Boulangier.

Your research didn’t dig deep enough.

Steve.

Thanks for this article. Filled in many gaps in my knowledge. Why no ES-175 and the laminated tops. Not carved, perhaps, but clearly an archtop. Key to the sound of Joe Pass, Herb Ellis (an ES-165), and Pat Metheny. Just delving deeper into jazz, I’ve recently purchased a 2001 Patrick James Eggle Derwent. For a short period, Eggle made archtops. He now specializes in his version of LP, S, and T models with lovely finishes and aged hardware. Exceedingly rare, but a marvelous instrument. Hand carved, tap tuned, 17″ lower bout, floating Benedetto pickup, no cutaway, with a stunning and bright acoustic voice. I’m grateful to a Kansas collector for pointing me in this direction.

Just wanted to mention that the early 1930s Martin archtops (C-1, C-2, C-3) did indeed have carved tops.

Good article, but deserves a followup on contemporary builders and archtop innovators like Linda Manzer, Tom Ribbecke (compliant rim), Ken Parker and others too numerous to name. The archtop continues to evolve.

Good overview, but a couple of points are worth mentioning: Matt Munisteri recently posted a YouTube video about the L-5. But he made some interesting observations while doing so. He said Nick Lucas and Eddie Lang both made extensive use of large, ladder braced flattops, despite their association with the L-5. Munisteri said that Lucas, in particular, never made the switch to the L-5 despite holding one in various publicity and catalog photos. And, as is well known, the Gibson Nick Lucas model, in both forms was not an archtop. Matt also pointed out that ladder braced flattops have a lot of similarities to archtops: The midrange emphasis; the cutting power; the attack and decay characteristics are very similar.

This sent me down a rabbit hole buying up vintage Harmony flattops. And my experience confirms the hypothesis. A Harmony H1260 Sovereign really does have similar qualities to not only its archtop Harmony equivalent H1310 Brilliant, but to the Gibson L-50 and L-75 as well. Which brings me to my second point:

Notwithstanding the David Rawlings effect, players who are archtop curious have very few affordable options for new guitars, particularly for purely acoustic instruments. Stated differently, Gibson has wholly abandoned the market they were founded upon. And no one has filled the role Harmony, Regal, and Kay once did. The Loar brand is in financial trouble; Eastman (unless something changed very recently) stopped making acoustic only archtops, as did Godin. And while Gibson launched the Epiphone Masterbilt line about a decade ago, the marketing team pushed the plugged in sound of these guitars. And not even a traditional pickup like a DeArmond, but a piezo setup. These guitars suffered from the neither fish nor fowl syndrome: Unconvincing as purely acoustic instruments to archtop veterans; and inferior as piezo amplified guitars when compared to equivalent flattops.

The bottom line is that someone not already familiar with archtops but curious about them face the prospect of buying used—always a risk with vintage instruments if you’re inexperienced (and sometimes even if you are)—or buying an expensive luthier built instrument.

I think there’s a gap in the market for purely acoustic archtops of the kind once cranked out by Harmony, solid wood but pressed and not carved tops and backs. Epiphone indeed took this approach 10 years ago, but as mentioned, they treated the acoustic tone as an afterthought.

That said, Guild currently offers the A150 Savoy, which features just that construction and a DeArmond Rhythm Chief pickup. They also have their line of laminate arched back/solid top flattops, as does Taylor. Either company should be able to use the same tooling to cost effectively build archtop guitars. Indeed, Guild describes on their website that they came up with the arched back flattops directly from their archtop guitars.

I would love to see Guild offer the A150 in purely acoustic form, and to offer at least one such instrument to their line. For similar reasons, and again they already have the tooling, Taylor could fill that gap in the market.

Anyway, just a pet rant from an archtop player. Thanks for sharing this article!

Great article but You forgot John Buscarino who worked for Bob Benedetto and Augustino Lo Prinzi and developed his own Archtops that compare with any of the greats–Joe Braccio