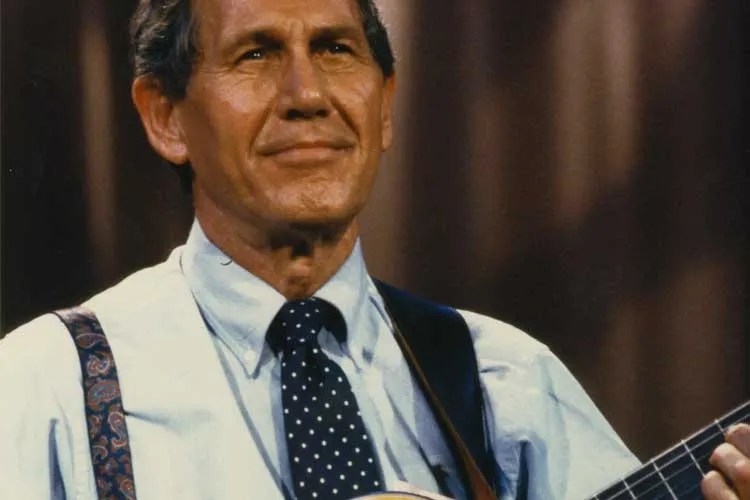

Interview: How Billy Strings Became the Most Electrifying Bluegrass Artist of His Generation—Without Leaving the Old Songs Behind

March 1, 2025: It’s Billy Strings’ second consecutive packed-to-the-rafters show at the 17,000-capacity Bridgestone Arena in his adopted home of Nashville. As he and his crack band trade fantastic fours on mandolin, banjo, fiddle, and guitar on songs like the modern classic “Dust in a Baggie,” the blinding “Highway Hypnosis,” the trippy FX showcase “Meet Me at the Creek,” and the wicked waltz “Hellbender,” it’s impossible not to imagine the spirits of bluegrass legends like Lester Flatt, Doc Watson, and Tony Rice looking down on the wondrous scene with a certain pride.

And perhaps some astonishment. At just 32, Strings is the first acoustic bluegrass artist in a generation—22 years, to be exact—to land a record at No. 1 on the Billboard Top 100 Album chart: his burning 2024 LP, Highway Prayers. (The last to do it was the O Brother, Where Art Thou? soundtrack, back in 2002.) Over the course of three nights, Strings performed for roughly 45,000 people. Just down the street, at the historic Station Inn—a regular roost for acoustic music legends since 1974, from Bill Monroe to Alison Krauss—the bluegrass gospel was being served to a much smaller congregation: capacity, 175.

Strings’ success is surely a testament to his extraordinary guitar playing, his convincing vocal delivery and harmony-rich arrangements, and his high-energy performance style. But it’s equally rooted in his earthy, hooky songs, which transpose the world-weary yet whimsical and often homesick themes of classic bluegrass into distinctly modern contexts: hard drug addiction; the slow ruin of alcoholism; battles with negative self-talk. It’s why so many fans—some call themselves “Billy Goats”—refer to his music as their “daily bread.”

And the Strings phenomenon goes far beyond Nashville. His spring tour found him headlining arenas across the States and alongside alongside Willie Nelson and Bob Dylan at the Outlaw Festival. Strings has also taken his post-psychedelic bluegrass gospel to sold-out crowds across Europe, and this summer’s Australian tour brings him to arena-sized venues in Melbourne, Sydney, Auckland, and Brisbane. He’s also a two-time Grammy winner for Best Bluegrass Album: Home in 2021 and Live Vol. 1 this year.

Now settled into married life and new fatherhood, Strings has reached milestones once unimaginable for a working-class kid from Lansing, Michigan. His latest triumph: the launch of two signature Martin dreadnoughts—both reviewed in this issue—following the quick sellout of his limited-edition Preston Thompson signature model in 2021.

I spoke with Strings shortly after his Bridgestone Arena shows to dig into his roots, his ever-expanding sound, and the lessons he’s learning along the way.

You’ve described being aware of bluegrass guitar as early as age two, when your father began playing Doc Watson songs on his D-28 around the house. How do you think that informed your early development as a player?

My first memories are learning how to just sort of hum tunes with my guitar while I played rhythm. When I was like six years old, I was my dad’s little rhythm player, playing tunes like Doc Watson’s “Salt Creek,” “Beaumont Rag,” “Black Mountain Rag—all those bluegrass standards. My dad would be playing the melody, and even more than, say, what measure we were on, it was the melody that signaled me which chord to go to next.

I spent those early formative years strictly playing rhythm and listening hard to those classic melodies. When I graduated to playing leads and melodies, it was still kind of like humming a little kid’s tune to me, but now I was actually doing it on my guitar. From listening and playing along, I just knew, even before I was ten, where the sounds could be found on the fretboard, so I could just pick out the melodies like I was singing “Mary Had a Little Lamb” or something.

ADVERTISEMENT

Was it intuitive for you to exploit the open strings in those fiddle-style melodic figures, or was it a matter of learning how to incorporate them?

Open strings are obviously really important in this music—all your money’s in the first five frets in bluegrass flatpicking. But no, I never had to think about whether the note was an open string or not. Either it would be an open string or it wouldn’t, but I didn’t have to think about it; it just came naturally based on what I had heard and seen my dad do. I feel really lucky that I started playing from that foundation of keeping the rhythm and letting the melodies sink in.

Sometimes my dad would capo up on the second fret, while I stayed in standard, which is a lot like the whole Doc and Merle Watson thing, where if one person’s playing an open E chord, the other player can capo on the fourth fret and play out of a C position, and exploit open strings there, too. Or, if you’re playing in the key of B, for example, you can just fly that capo up to the fourth fret, and you suddenly have all your open-string G-position licks available to you. I love that.

That’s not to say that closed voicings aren’t great for bluegrass, but it’s a very different sound. There are some great players that used closed voicings: Chris Eldridge can do that, Michael Daves does that a lot, and of course Tony Rice did a lot of that later on when he started hanging out with David Grisman and learning a lot more jazz theory and voicings.

Here’s a good example: On the tune “Fish Scale,” from those great early David Grisman Quintet recordings, Rice is playing that head in the first five frets, with lots of open strings.

But then, later on in his career, you can actually hear him playing that same basic melody in closed positions up on the seventh fret. I find that so interesting as he got more familiar with the fretboard and started exploring jazz chords and arpeggios, that he finds different fingerings to play the same tune. Tony was always refining his craft, you know?

You seem to be taking a similar path, fusing your bluegrass roots with a modal approach to rock-style soloing. And likewise, you’re still a serious student of guitar, even with all the accolades that have come your way.

It’s funny. I’ve been playing my whole life, right? I grew up playing bluegrass around a campfire, and I jumped right into learning fiddle tunes and stuff like that. I thought everyone did that. Music was just like oxygen around our house. It was what you needed to breathe, and luckily I always had a good ear—I could hear something and immediately play it.

I first hit the road touring when I was 19, and I literally haven’t stopped. It’s been an amazing ride, but at some point I came to the realization that I really didn’t know what the hell I was doing, at least from any theoretical point of view. I didn’t know any of the names for anything I was playing. I’m being thrown into recording sessions with people like Béla Fleck, and all these players are talking about how the tune is built from the chords of harmonic minor, or whatever—all this heavy musical language. I felt like I was the little infant in the room that didn’t really know what anybody was talking about, but was pretending to [laughs]!

I also started getting tired of playing the same types of licks and sounds over and over. I had to have a little talk with my licks: “I love you, licks. You got me here, but you really need some new friends.” So, a couple of years ago, I decided to do something about it, and I started taking proper, regular guitar lessons for the first time, with real assignments and practice routines, with the folks at Sonora Guitar Intensive.

Bryan Sutton has been a huge influence, as has my main teacher now, Robb Cappelletto, who has me learning pieces by Bach and Coltrane, stuff I never would have been exposed to before, and doing it all with flatpicking technique. It’s made me realize how helpful a real regimented and regular practice routine can be. It’s a little weird that I had never done that before. I mean, I had a Grammy before I even started taking proper guitar lessons [laughs].

I can see why that’s an odd position to be in, though it must be said that your playing, even early in your career, was always extremely high-level.

ADVERTISEMENT

I appreciate that, man. But in a way, it did become a little uncomfortable having so many people tell me how good they thought I was when, really, I hadn’t actually impressed myself all that much yet. When I’d hear those kinds of compliments, I’d think, um, have you heard Jake Workman play? Do you know Bryan Sutton? What about Molly Tuttle? And have you listened to Cody Kilby or Jake Stargel? I have a lot of people coming to my shows, and I’m really grateful for that, but I ain’t a better player than those cats, man. Thing is, I want to be as good as them—or maybe I should say I want to be that good at being me. That’s it. I want to impress myself, and I feel like I’ve never fully done that yet.

Now, I know it’s not all about technique. My first motivation to play the guitar came from watching what would happen when friends of my folks would come over and my dad would be playing all these great tunes on his Martin, and just seeing the joy on everyone’s faces. As a little kid of three or four years old, I knew I wanted to do that, too, and that’s still a big part of what I do. Thing is, though, once you get into bluegrass, and you start wanting to learn how to play “Black Mountain Rag,” you quickly realize that you’re going to have to develop some real technique.

To this day, I’m very aware that when I put the hours in at home and really practice diligently, I’ll have a much better hold on things when I’m back out there onstage, and because of that, I can bring even more joy to people. And it’s because I’m warmed up; it’s directly because of all the practice that I’m able to play as freely as I do. It’s not just for technique’s sake alone.

It’s really interesting to me the way you apply flatpicking to more bluesy, even fusion-style electric guitar territory, using the K&K Double Helix and Kemper Profiler, which is the last thing one expects out of a dreadnought.

Well, when I was a teenager, I was actually in an original rock band, and I loved playing that riff- and blues-based stuff like Black Sabbath, Hendrix, and Led Zeppelin—playing my little Squier electric through a Pignose amp out in front of the gas station. Thing is, I just don’t feel as comfortable on an electric guitar, so having the Double Helix pickup in my acoustics lets me switch back and forth from rock soloing to bluegrass picking without changing guitars. Bending on those 13-gauge strings is definitely the biggest challenge. Even 12s are no joke to bend on, but the 13s are really hard on my hands. Just lately, I’ve been working on sliding up to those same notes that you’d typically bend up to on an electric, and that’s been cool. I do like to step on the fuzz pedal and really soar. It’s such a different feeling from bluegrass technique.

The arenas you’ve been playing lately certainly aren’t typical venues for bluegrass artists. Between that and the whole celebrity buzz around you, does it feel like a challenge to keep it all down to earth?

Back when I first started my career, I used to wear a suit and slick my hair back, because that’s how all the old bluegrass guys looked, and I was just so knocked out when I saw those kinds of players at festivals for the first time. A part of me thought that I had to do that, but eventually it felt inauthentic, like I was putting on a costume.

These days it feels more comfortable for me to strip all that stuff away and keep my head in my guitar and my singing, and try to outmaneuver most of the extra stuff that comes along with this industry, but I admit it’s a lot to handle. Look, I love having our amazing light show and our awesome production. The people in our crew are really talented, and they provide a really entertaining show for the folks. That said, it’s nice to just strip it down, shine a single light on me and the band with just our fully acoustic instruments, and stand around a microphone and sing. So we make it a point to do that for a few songs at every show. At the end of the day, most everything I do comes from Doc Watson, and so that’s home.

If anything, what’s changed things the most for me is becoming a dad last year. Music has always been my main thing. It’s always been how I’ve gotten through the tough times and how I’ve made friends. I’m a pretty shy person, but I pick up the guitar, and it becomes a lot easier for me to talk to people. During this wild rise of the last few years, there’s been a lot of pressure. I’m really hard on myself about the music, and I genuinely want to sing and play really well every night. Plus, I’ve got a lot of plates that I’m spinning in the air between being a bandleader and helping to manage a business. I try to keep everybody who works with me happy and try to keep everybody entertained at every show. It’s a lot.

But lately I find that if I’m onstage stressing about everything being perfect, I can look up and imagine my little boy’s big gummy smile when I get home, and it really frees me to not worry so much. I used to think that I wrote my best songs when things were difficult or painful for me, but lately I’m aware that I’m playing better and much more freely than I ever used to, and it’s because I’m just in a better place in my life.

ADVERTISEMENT

Wired for Bluegrass

“It’s Tobe Bean’s world—I’m just living in it,” jokes Billy Strings. Bean, the veteran guitar tech whose CV includes stints with artists as diverse as John Mellencamp and Marilyn Manson, says of his boss, “I’ve worked for a lot of amazing guitar players in my time, but I’ve never seen anybody play like Billy Strings.”

With two mammoth full-sized processing racks behind him, Bean hands me Strings’ no. 1 Preston Thompson DBA dreadnought, strung with 13s, and asks me to try bending a few notes. He switches to the guitar’s K&K Helix soundhole pickup, which Strings uses to drive a Kemper Profiler Soldano SLO-100 patch for electric-style lead work. “Thing is, the kid absolutely wails on these,” shrugs Bean. “Bending notes like Hendrix. It’s insane.”

Strings’ massive offstage processing towers may appear to be overkill—and in lesser hands, they might be. But his precise phrasing and smart use of effects yield punchy rhythm work, psychedelic detours, and a lead tone that, as Bean puts it, hits “like the throaty neck pickup on a Gibson Les Paul or ES-335.”

Strings’ main acoustic onstage is a 2017 Preston Thompson DBA, nicknamed Frankenstein for its many mods and Old Faithful for its years of service. Like most of his acoustics—including his backup Thompson, aka Bride of Frankenstein—it’s outfitted with three transducers: a K&K Pure Mini pickup; a Shure WB98H/C clip-on mic for the house mix; and a K&K Double Helix in the soundhole for electric tones, switched on and off via a discreet lower-bout toggle. “Some people may find that a little blasphemous on such a nice guitar,” Strings says, “but it’s what works for me.”

Each acoustic’s K&K Pure Mini gets added warmth, gain, and EQ shaping via a Grace Audio BiX preamp. Like his blinged-out Martin D-45, the two Thompsons are outfitted with D’Addario XS phosphor bronze (.013–.056) strings. Strings uses Elliott Capos—favoring the fourth fret “for playing all your G licks in B”—and BlueChip TP48 picks for precise flatpicking and a silky top end.

ADVERTISEMENT

With a Two-Rock amplifier in tow, and the Kemper Profiler mentioned above, it’s no surprise that the electric-curious Strings calls on dozens of boutique effects pedals as well. Among his favorites are his signature Chase Bliss Wombtone; Source Audio Nemesis Delay and C4 Synth; DigiTech Polara, NativeAudio Pretty Bird Woman chorus/vibrato; Eventide H9 multi-effector; and Electro-Harmonix Freeze, PitchFork, and Intelligent Harmony Machine. Strings controls the chaos from his onstage perch with a clutch of expression and volume pedals and an imposing RJM Mastermind GT-2 MIDI Switcher, along with a Radial SW4 Balanced Switcher and Radial JX44 Guitar Signal Manager and Switcher.

One guitar remains untouched: Strings’ cherished 1940 Martin D-28, free of pickups or mods, and always close at hand for pre-show warm-ups and hotel room picking. It also served as the blueprint for Martin’s new D-28 Billy Strings and D-X2E signature models.

“The Martin D-28 is just so American—it’s like baseball or something,” says Strings. “It’s the sound that’s captivated bluegrass guitarists for decades, including me. —JVR

This article originally appeared in the July/August 2025 issue of Acoustic Guitar magazine.